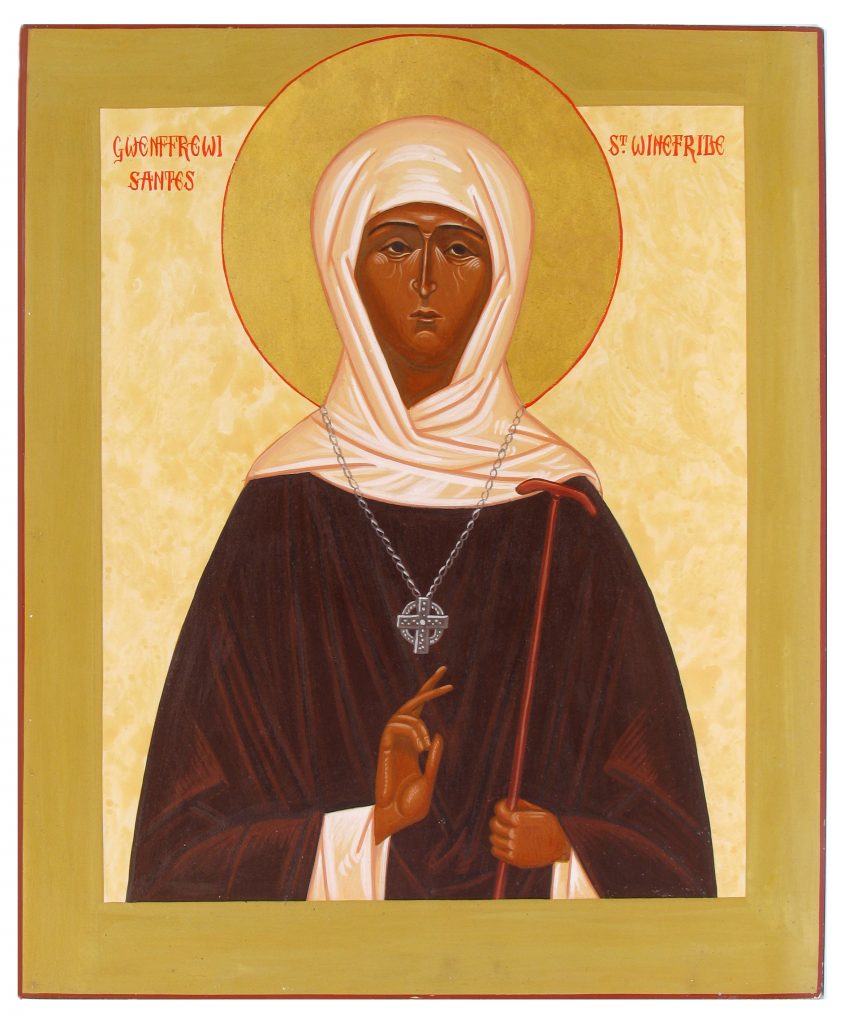

3 November

Saint Winefride emerges from tradition when, in 1158 the Abbot of Shrewsbury thought her to be of sufficient importance so as to buy her relics from Gwytherin, her home in North Wales. We have two late medieval vita (lives), the first one dating from 1135c is anonymous and the second was written by Robert, prior of the Benedictine abbey of SS Peter and Paul in Shrewsbury 1138-42. This vita has a fascinating section on the translation of the relics from Gwytherin to Shrewsbury. It has been suggested that the main source for both lives was a Latin life of St Beuno which Robert mentions in chapter 22 of his Life of St Winefride, but this is no longer extant. It also seems evident that each had independent sources as well.

The Life of the Saint

Born probably between 610 and 620, Winefride was said to be the child of Tyfid and Gwenlo who were of noble birth. As a child she resolved to dedicate her life to God by living a life of chastity and prayer. Winefride was martyred as a teenager one Sunday as St Beuno, Winefride’s priestly uncle and spiritual father, was preparing to serve the Liturgy on the Feast of Saint Alban (June 22nd). A young prince named Caradog, hot and thirsty from hunting called at the cottage for something to drink. Finding the beautiful Winefride alone there he attempted to seduce her. Winefride fled down the valley to the chapel of Saint Beuno pursued by Caradog. He caught her by the chapel door and in his rage at being rejected he beheaded her. Where her head fell a spring of water gushed forth and thus created the Holy Well that has been a place of pilgrimage ever since. Saint Beuno replaced her head and restored her to life after he had pronounced a curse on Caradog who, it is said, “melted away like wax before the fire”. One mark was left as a reminder of the miracle-a slender white scar like a thread encircling her neck. It was from this, according to one account, that she received the name of Winefride. (Wen or Gwen = white, she is said to have been originally called ‘Brewi’).

After her martyrdom, Winefride continued to live a holy life first as a hermit and then as a nun at Gwytherin, a remote place in Denbighshire, firstly under the Abbess Theonia then as abbess over eleven nuns. She remained as superior at Gwytherin until her death fifteen years later. Robert, Prior of Shrewsbury, in his vita adds she also founded a convent at Saint Beuno’s church in Holywell and gives an account of her death. “When the time came for her departure from this world, Windefride bade the virgins to keep their vows of chastity and guard their faith. Receiving the last sacrament from the Abbot Eleri, she died at the beginning of November and was buried in the churchyard at Gwytherin next to Tenoi and with the confessors Senanus and Chebius and other holy men and women. After her death many came to Gwytherin to be cured of their infirmities.” One of the first books ever printed in English by William Caxton circa 1485 was a translation of Prior Robert’s vita, The life of Saint Winefride in which he states, “….and after the hede of the vyrgyne was cut of and touchyd the ground, …sprang up a welle of spryngyng water largely enduring unto this day, whiche heleth all languors and sekenesses, as well in men as in bestes; whiche welle is named after the name of the vyrgyne and is called Saint Wenefredes Well…”

Historical references

It is surprising to find that the compilers of the Domesday Book in 1086 failed to mention either well or church, but in less than a decade we have the first written record of a church at Holywell in 1093. It was granted first to Saint Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester, then by Llywelyn Fawr to Basingwerk Abbey. Such was the reputation of the miraculous power of the spring that by the end of the Middle Ages it was described as one of the wonders of Wales.

Saint Winefride’s Well is the only place that can be identified in the late medieval romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and the nineteenth century poet Gerard Manley Hopkins expressed its importance as a place of pilgrimage,

“Here to this holy well shall pilgrimages be,

And not from purple Wales only nor from elmy England,

But from beyond seas, Erin, France and Flanders, everywhere,

Pilgrims, still pilgrims, more pilgrims, still more poor pilgrims.

. . . . . . . . . . .

What sights shall be when some that swung, wretches, on crutches

Their crutches shall cast from them on heels of air departing

Or they go rich as roseleaves hence that loathsome came hither!”

King Richard I (Richard the Lionheart) visited the site in 1189 to pray for the success of the crusade. The English monarchy had an almost continuous link with the shrine for nearly 140 years (1398-1536/7. They employed a priest for daily prayers and masses to be said for themselves and the souls of their ancestors in their chantry. Edward IV came on pilgrimage and Richard III, in 1484, ‘out of devotion to St Winefride’ provided a generous annuity for the maintenance of a chantry priest. Henry V was said by Adam of Usk to have travelled there on foot from Shrewsbury in 1416 after his victory at Agincourt and Henry VII renewed the financial provision after his victory at Bosworth in 1485. Until the Reformation Henry VIII maintained several chaplains.

Development of the well house

In the late 15th century a chapel overlooking the well was built, it is thought, by Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII, which now opens onto a pool where pilgrims may bathe to this day. Some of the structures at the well date from the reign of King Henry VII or earlier. A fine example of late Perpendicular style of architecture the graceful arches rising above the sides of the well have the motifs of Catherine of Aragon, the Stanley family and others. The five angular recesses were probably inspired by the five porches of the pool of Bethesda.

Survival of the well through the Reformation

King Henry VIII ordered the shrine to be destroyed but, miraculously much of it survived, and pilgrims continued to come and pray there through the dark days of the English Reformation. The unbroken records of pilgrimage to this holy well throughout the 1,300 years since the martyrdom of Saint Winifrede undoubtedly make it the oldest one in the British Isles in continuous use.

Translation of the Saint’s relics to Shrewsbury Abbey

The Domesday Book does, however, record that an abbey was being built at Shrewsbury by Roger Montgomery. By 1130 the abbey church was ready for consecration but did not have any holy relics and the monks were envious of the many said to be in Wales. Robert in his vita tells of one of the Shrewsbury monks who fell sick. Prayers for his recovery were offered to no avail at both Shrewsbury and Chester. The Chester monks held a procession before prostrating themselves before the altar and singing, “the seven psalms”. During this vigil Saint Winefride appeared to Radulphus, the Sub Prior, asking him to celebrate mass in her church at Holywell. After forty days the condition of the monk worsened and Radulphus went with one of the other brothers to the shrine, “and the instant Mass was sung, the infirm brother at Shrewsbury was restored.” In thanksgiving the monk went to shrine, “to pray in the church, to drink of the fountain, and to bathe in its waters.” As a direct result of this healing the monks of Shrewsbury began negotiations to obtain the relics of St Winefride for their abbey. With the consent of the Bishop of Bangor Herebert, Abbot of Shrewsbury dispatched Prior Robert and another monk called Richard to Wales. The mission was accomplished by prayer (and payment) in 1138. The relics were recovered, as psalms were chanted by a group of monks, and translated to Shrewsbury.

The actual route of the seven-day journey is not known, however there is a tradition that they rested at Woolston near West Felton, where there is another St Winefride’s Well. This is almost certainly the place mentioned in Prior Robert’s account, “And when they came to a place about ten miles from Shrewesbury they rested & tarried there. When they should have departed they could not remove the bones so they counselled together and concluded that the bones should he washed at that place. There was no water: but a fair well sprang up there which still runs to this day like to the other well. In this well they washed the bones of the blessed Saint Winefride. Ever after the stones that rest in that water are marked as it were with drops of blood.” William Caxton in the fifteenth century recorded various healing miracles that had occurred here.

The relics of Saint Winefride were welcomed to Shrewsbury with great rejoicing in 1138 and placed in the church of St Giles whilst a shrine was prepared in the Abbey. Great throngs of pilgrims venerated the relics as they rested at St Giles and miracles were witnessed including the healing of a cripple. The relics of St Winefride were finally translated to the Abbey on 19th September 1138. “On the appointed day, the brethren proceeded with crosses and candles and a vast crowd of people. The most sacred body of the blessed virgin Winefride was brought out: the whole multitude fell on their knees, and many, from the excess of their joy, could not refrain from tears.”

Devotion to Saint Winefride in Shrewsbury

The shrine of Saint Winefride in Shrewsbury Abbey became a popular place of pilgrimage and its sanctity was demonstrated in many miracles. Devotion to St Winefride is clear from the iconography of the early 14th-century pulpit that survives on which she can be seen with St Beuno in one of the panels. Popularity grew in the 14th and 15th centuries and Abbot Nicholas Stevens (1361-99) built a new shrine for her relics in a chantry chapel for the benefit of the many pilgrims. Shortly after he (illegally) obtained the relics of St Beuno. In 1398 the Archbishop of Canterbury emphasised the importance of her feast-day on November 3rd ordering that it be kept with nine lessons, and his successor in the early 15th century added further devotions to the occasion. Henry V planned to establish a chantry to the saint but died before he could carry this out. Richard, earl of Warwick on his death in 1439 instructed his executors to present a gold statuette of himself to adorn St Winefride’s shrine. In 1463 Abbot Thomas Mynde established a chantry at St Winefride’s altar to pray for the soul of Henry and his heirs, and set up a perpetual guild for its maintenance in 1487.

The desecration of the shrine

At the Reformation all church property was valued so that the king could claim the taxes hitherto paid to the pope. The death of Henry VIII in January 1546-7 freed the reformers from the restraint of a King who had remained attached to much of the traditional piety of the church. Edward VI and his ministers went much further, the chantries were dissolved and the parish churches were plundered. English services were introduced to replace the Latin ones and relics, images, wall-paintings and windows were desecrated or smashed in what is estimated to have been the greatest destruction of art in the history of European civilisation. The shrine of Saint Winefride at Shrewsbury was destroyed, the relics scattered and only part of her thumb bone survived. It was found in Rome in 1852, entered in the register of relics. When it was located half was taken back to Shrewsbury where it was again divided; one part is now in a silver reliquary in the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Shrewsbury and the other is kept by the religious community at Hollywell. A fragment possibly of the shrine or of a reredos was recorded by the Rev. Blakeway in the early nineteenth century.

Continued veneration at Holy Well

In the 17th century the shrine at Holywell became known as a symbol of the survival of Catholic recusancy in Wales. From early in their mission to England, the Jesuits supported Holywell. King James II visited with his wife Mary of Modena during 1686, after several failed attempts to produce an heir to the throne. Shortly after this visit, Mary became pregnant with a son, James. Doctor Johnson, who passed through Holywell in 1774, noted in his Diary that it was the most copious natural spring in Britain turning no fewer than nineteen mills. Princess Victoria, staying in Holywell with her uncle King Leopold of Belgium, also visited the Well in 1828.

Well at Woolston

Saint Winefride’s Well at Woolston is another remarkable survival of the Reformation. The half-timbered chapel over the well was, like the larger one at Holywell, probably built at the expense of Margaret, Countess of Beaufort, wife of Henry VII. The timber has been scientifically dated to 1478-82. Although associated with St Winefride since the translation of her relics, it has an earlier association with Saint Oswald. The Domesday Book refers to it as Osulvestune (Oswald’s Stone.) It is possible that the well at Woolston had already been a holy well for centuries dedicated to Saint Oswald.

Orthodox Pilgrimage continues

Annual pilgrimages to both Holywell and Woolston by the Orthodox communities of Saint Barbara in Chester and the Holy Fathers of Nicaea in Shrewsbury have been taking place for nearly forty years now. Once again representatives and descendants of the pre-schism Church of Saints Beuno and Winefride are able to venerate these great saints of Wales.

Pointing to the five centuries that elapsed between the events and the first written accounts many have consigned the story of St Winefride to legend. In the Orthodox Faith the veracity of a Saint is not disputed in this way; “the occupation of a Saint” is, as T.S.Eliot put it, at the frontier between what we know and that which is beyond us. Saint Winefrides’ Well exists as a meeting of the ‘timeless’ with ‘time’, the kairos that marks the frontier of consciousness beyond which words fail, though meanings still exist. Here in this holy place the pilgrim apprehends meanings that exceed both language and comprehension. Thus the words of Christ are realised in His saints and are continually reiterated in the miracles associated with Saint Winefride – “the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, and the poor have the Gospel preached to them.”

“If you came this way,

Taking any route, starting from anywhere,

At any time or at any season,

It would always be the same: you would have to put off

Sense and notion. You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity

Or carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid.”

T.S. Elliot

Christopher Jobson

The Troparion of Saint Winifride in Tone 4.

Suffering death for your virginity, O holy Winifride, through God’s mercy your body was made whole and restored to life. Thy healing grace flows in streams of living water. Pray to God for us, that our souls may be saved.

Saint Winefrid Pilgrimage route from North Wales to Shrewsbury